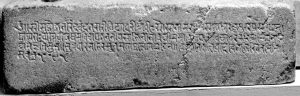

IN03165 Koṭṭangē Rock Inscription 2

The inscription is engraved on a flat rock in the village of Koṭṭangē in the Mādurē Kōraḷē of the Vǟuḍavili Hatpattu in the Kuruṇǟgala District. When Senarath Paranavitana visited the site in 1931, the rock lay just within the boundaries of a coconut plantation called the Ōgoḍapola Estate in the Delviṭa Group. It was at that time completely buried under about two feet of earth, soil having washed down the hillside and covered the rock. However, a local villager who had seen the rock some years previously alerted Paranavitana to its existence. Paranavitana was then able to remove the earth and reveal the inscription, which he copied for the Archaeological Department. The existence of an inscription at this place had previously been mentioned in the Return of the Architectural and Archaeological and other Antiquities existing in Ceylon, which was published by the Ceylon Government in 1890, but it is not clear whether the inscription in question was the present record or IN03164, which is engraved on another rock in the same vicinity.

No date is given in the inscription. It opens with a Sanskrit verse, a significant portion of which is no longer legible. The rest of the inscription is written in Sinhalese and records that a mahāthera of the Vilgammuḷa fraternity, whose name is obliterated, granted to the saṅgha the pamuṇu village of Kaḷama and some other lands belonging to him. This mahāthera is said to have been the grandson of a personage who belonged to the Lämäni family but, unfortunately, the name of the latter is not preserved. We may presume that the mahāthera was a grandson of Loke Arakmenā, to whom the village was originally granted by Lokeśvara, as recorded in the other inscription at this site (IN03164). This supposition gains further strength from the fact that, as shown by the title ‘Arakmenā’, general Loke belonged to the Lämäni stock; his connection with the Vilgammuḷa fraternity is also shown by the stipulation in the first inscription that any disputes concerning the lands in question were to be settled by a mahāthera of that religious institution.

IN03153 Saṁgamu Vihāra Rock Inscription

The inscription is cut into the rock near the ancient Buddhist monastery situated on the low, rocky hill by the Meddeketiya tank at Saṁgamuva, a village about two miles to the north-east of Gokarälla, in the Häḍahaya Kōraḷē of the Kuruṇǟgala District. A series of over one hundred steps, cut into the bare side of the rock, lead up the side of the hill to a plateau, upon which stand the ruins of an old stupa and other monastic buildings. The inscription is engraved at the top of the steps, to the left as one ascends the hill. It was copied for the first time by Senarath Paranavitana in 1931 (see Archaeological Survey of Ceylon Annual Report for 1930–31, p. 5). The text is written in Sinhalese, apart from the last four lines, which consist of a Sanskrit verse in the Vasantatilakā metre, though nearly half of this verse is no longer legible.

The inscription is of exceptional historical importance, since it records an alliance between two princes called Gajabāhu and Parākramabāhu, who can be identified as Gajabāhu II (r. 1131–1153) and the future Parākramabāhu I (r. 1153–1186). The Mahāvaṁsa records how Parākramabāhu, after consolidating his position in the principality of the Dakkhiṇadesa to which he succeeded on the death of his uncle Kittisirimegha, undertook a campaign against his cousin Gajabāhu II with the object of making himself ruler of the island of Sri Lanka. Eventually, the two princes came to a peace settlement, as recorded in the present inscription. The two princes speak in the first person in this inscription. After introducing themselves by name, they come to the matter of the agreement. The first clause states that they will not wage war against each other for the rest of their lives. Although now partly damaged, the second clause seems to declare that, whichever prince dies first, his possessions will pass to the surviving prince. Since Gajabāhu was by some margin the older of the two, this clause essentially amounts to him bequeathing his kingdom to Parākramabāhu. The third clause is now almost completely illegible. By the fourth and final clause of the treaty, the two princes enter into an offensive and defensive alliance, declaring that any king who is an enemy of one of them, is an enemy of both. Paranavitana interpreted this clause as being directed against Mānābharaṇa, the ruler of Rohaṇa, who also had designs on Gajabāhu’s throne. The agreement concludes with imprecations against both princes if they act contrary to its terms. It is not clear why this record was engraved at the Saṁgamu Vihāra. Although it was within the territories under Parākramabāhu’s rule, there is nothing to prove that the place was close to his residence, even temporarily. Paranavitana posited that the treaty may have been brokered by a monk who resided at the vihara but this is only conjecture.

Sohagpur Jain inscription of Ajayavarman dated year 1244

Sohagpur (District Hoshangabad, Madhya Pradesh). Jain inscription of Ajayavarman dated year 1244.

OB03104 In̆dikaṭusǟya Copper Plaques

Mihintale, Sri Lanka

IN03128 In̆dikaṭusǟya Copper Plaque Inscriptions

In 1923, ninety-one inscribed copper votive tablets were found among the ruins of the Indikatuseya stupa at Mihintale. The tablets were discovered by the Archaeological Department of Ceylon during the restoration and rebuilding of the dome of the stupa. It appears that they were originally deposited in the relic chamber but became scattered when the stupa was raided by treasure-seekers, which would also explain the presence of some Dutch stivers in amongst the medieval copper tablets. Most of the tablets are about 0.8 mm in thickness and are inscribed on one side only. Some bear traces of gilding. The majority are completely intact but a few are broken or have missing corners. On palaeographic grounds, they can be dated to the eighth or ninth century A.D. The inscriptions on the tablets are extracts from Buddhist texts of the Mahāyāna school. Indeed, forty-six have been connected with specific passages in the Pañcaviṁśati-sāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā (nos. 1–46). A further fifteen have been found to quote from various passages in the Kāśyapa-parivartta (nos. 47, 48, 50–54, 57, 58, 61, 63, 67, 69, 76 and 79). The language of the inscriptions is Sanskrit but they are written in Sinhalese characters. The tablets are therefore significant epigraphical rarities, since there are few surviving examples from the medieval period that show the transcription of Sanskrit in Sinhalese script. However, the scribe does not appear to have been overly familiar with Sanskrit and, as a result, the inscriptions on the plaques often diverge slightly from their source texts.

OB03097 Kuccavēli Inscribed Boulder

IN03120 Kuccavēli Rock Inscription

The inscription is carved on the sloping side of a gneiss boulder, which stands just to the west of a larger cluster of boulders and caverns on the beach at Kuccavēli (Kuchchaveli) – a small fishing-village in Kaḍḍukkuḷam East, twenty-one miles to the north of Trincomalee. To the right of the inscription, an area of the boulder’s surface measuring about four feet (121.92 cm) square has been partitioned into sixteen compartments of equal proportions, into each of which has been carved in low-relief a representation of a stūpa. The inscription is written in Sanskrit and consists of two verses in the Upajāti and Vasantatilakā metres. The palaeography indicates a date later than the fifth century A.D. and earlier than the eighth. From the degree of development in the script, Senarath Paranavitana tentatively ascribes the record to the seventh century A.D., making it one of the earliest Sanskrit inscriptions in Sri Lanka. The contents of the inscription do not furnish any more precise information about the date. It simply states the pious wish of the author that, by the merit he has gained (presumably through making the carvings on the boulder), he may become a Buddha in the future for the deliverance of suffering humanity.

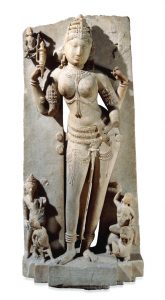

Inscription of Bhoja on a standing figure of Ambikā

Dhār (Madhya Pradesh). Inscription on the pedestal of the Ambikā in the British Museum (Courtesy: Trustees of the British Museum, no. 1909,1224.1 and ZENODO).

Standing figure of Ambikā with an inscription of Bhoja

Standing figure of Ambikā from Dhār mentioning king mentioning king Bhoja. (Courtesy: Trustees of the British Museum, no. 1909,1224.1).